Armstrong’s Inventions

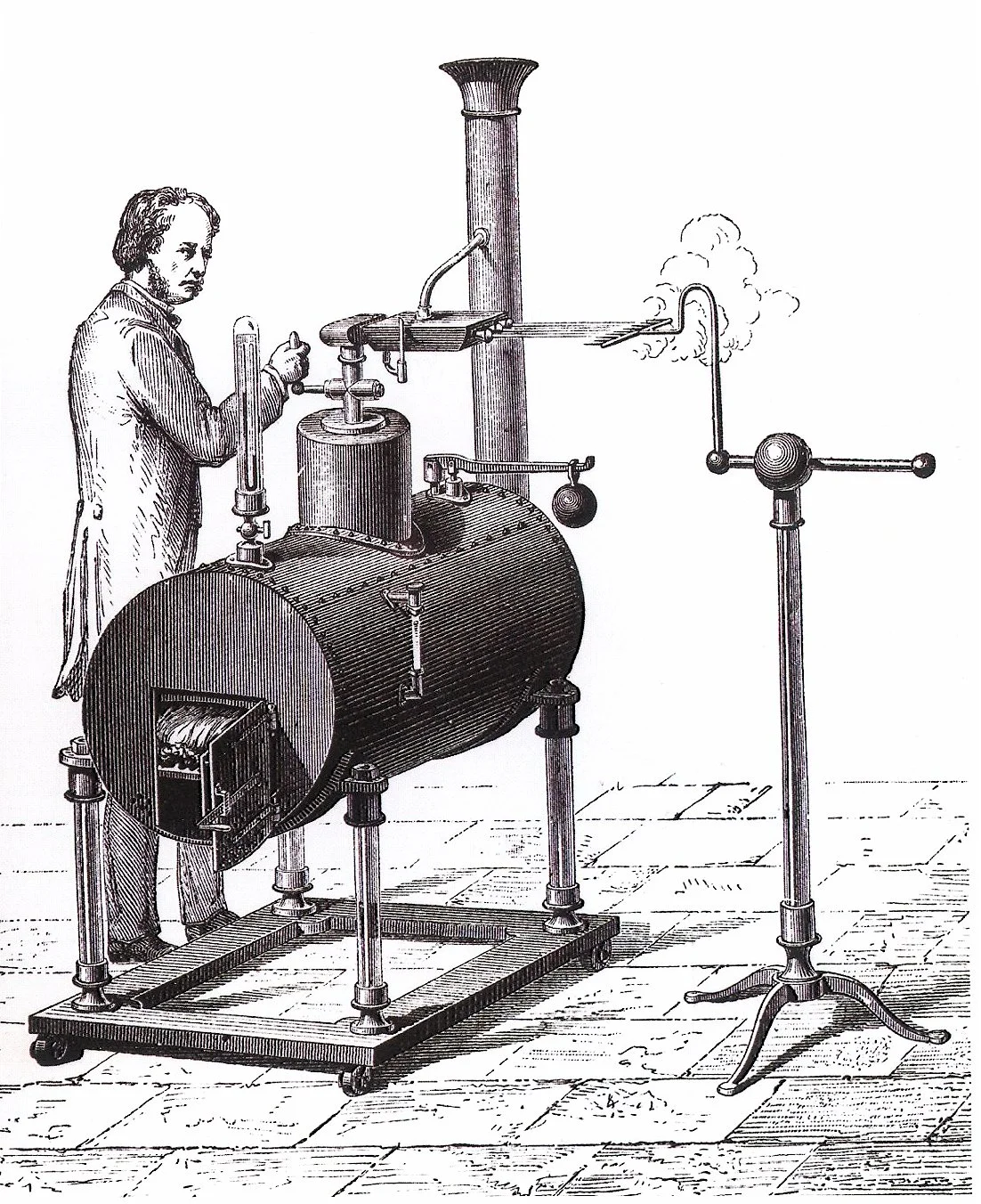

In 1842 Armstrong demonstrated his ‘hydroelectic machine’ at the London Polytechnic Institution. It produced frictional electricity from steam and drew fascinated crowds of onlookers.

From an early age, William Armstrong was obsessed with finding out how things worked and devising ways of making them operate more efficiently.

This led him to a string of inventions, starting with a water-driven rotary engine, and progressing to the development of hydraulics and hydroelectricity.

For many years he was best known in scientific and engineering circles as the inventor of modern artillery.

Hydraulic machinery: cranes, bridges and dock gates

Armstrong’s great passion in the scientific field was harnessing the power of water to drive machinery, and this led to his first great invention, the hydraulic crane, and later the ‘accumulator’, an effective device for storing water power.

‘By this invention, hydraulic machinery was rendered available in almost every situation,’ noted The Times. ‘It has come into extensive use for working cranes and hoists, opening and shutting dock gates, turning capstans, raising lifts, etc … In the navy its applications are almost infinite.’

Among many other applications, the technology was used to operate the Swing Bridge in Newcastle, which replaced an old stone-arched bridge and was designed to revolve on its axis to allow the largest ships of the time to pass through and steam upriver. It gave Armstrong a gateway to the sea – the prelude to opening a shipyard at Elswick.

The Swing Bridge had its busiest ever year in 1924, being opened more than 6,000 times. By the early 21st century the number of openings had exceeded one quarter of a million.

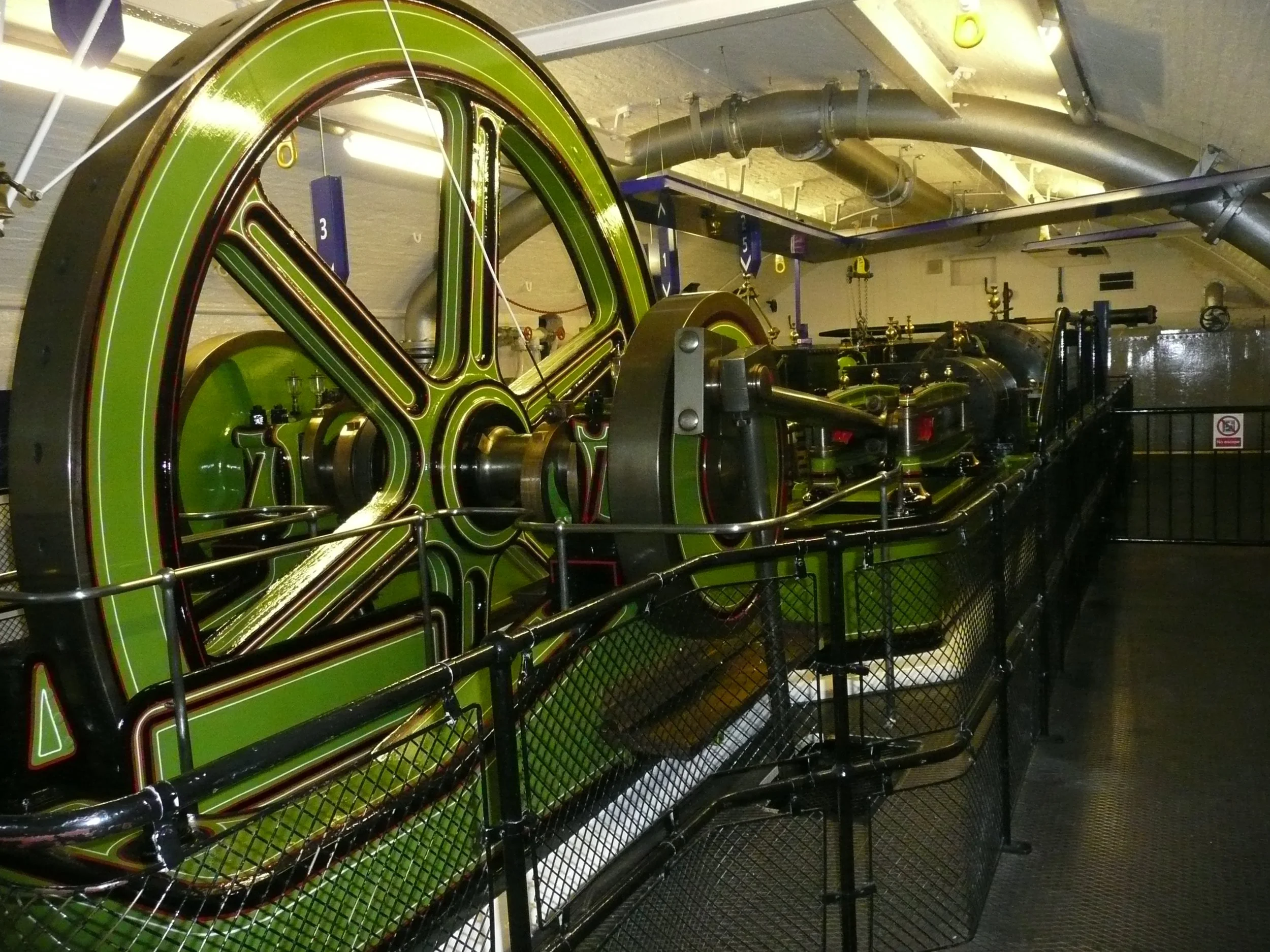

When London’s Tower Bridge opened in 1894, the mechanism for operating its giant bascules was driven by six of Armstrong’s accumulators.

The original Tower Bridge machinery can be viewed in a nearby museum, the Victorian Engine Rooms.

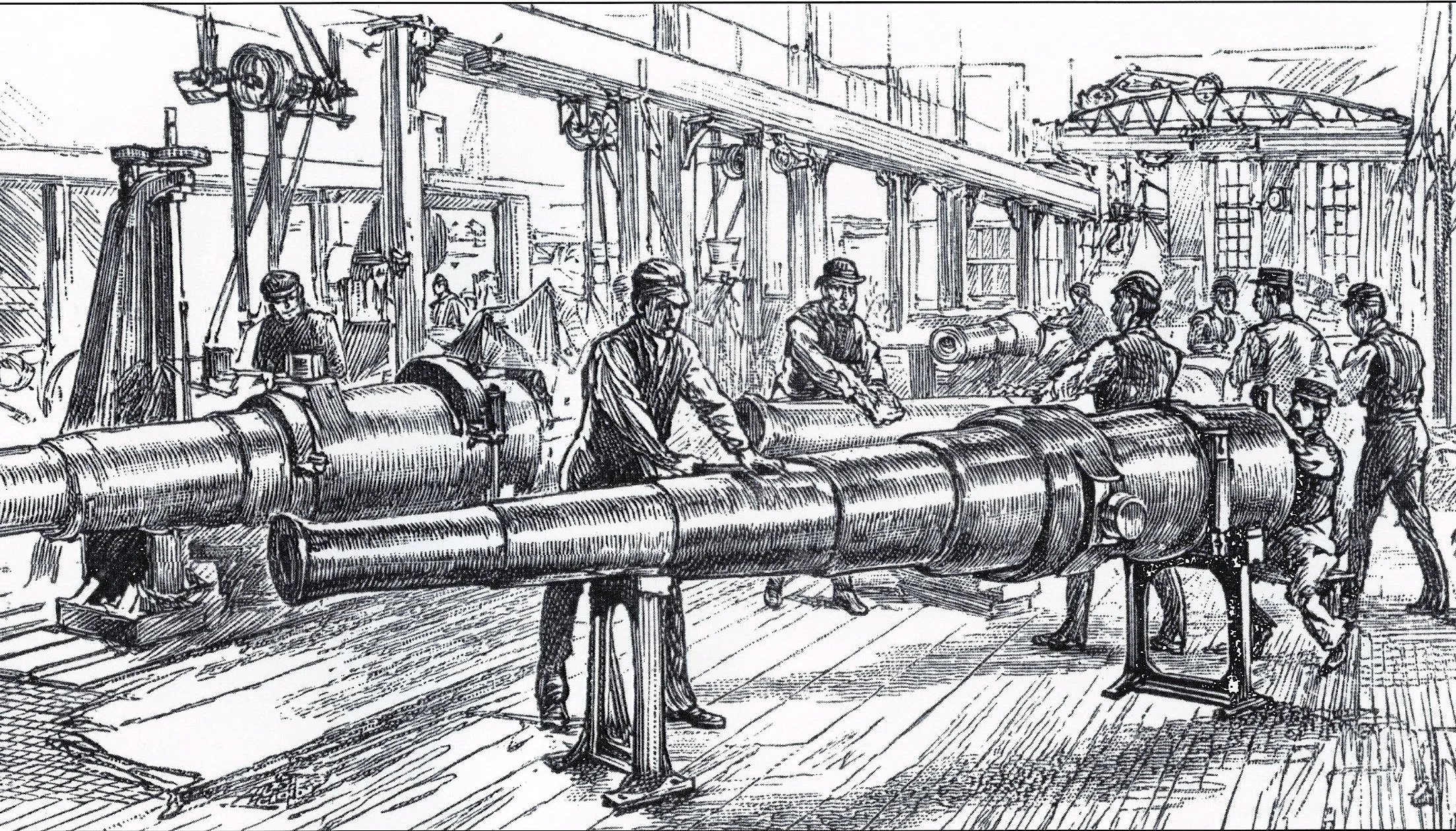

Employees at Elswick Works assembling guns designed by Armstrong and constructed on the ‘coil’ principle, for use on warships.

Guns and ships

Following the disastrous performance of British artillery in the Crimean War (1853–56), Armstrong designed a completely new kind of battlefield gun based on the well-established sporting gun. Replacing the cumbersome smooth-bore cannon that had to be dragged through the Crimean mud, the Armstrong gun was lightweight with a rifled bore and fired shells rather cannonballs. This revolutionised the speed and accuracy with which the projectiles could be delivered, and the gun was swiftly adopted by the British Army.

Armstrong was given a knighthood in recognition of his achievements in gunnery. He was made Engineer of Rifled Ordnance to the War Department and Superintendent of the Royal Gun Factory at Woolwich, but he fell out with the conservative army officers at Woolwich, and after a few years returned to Newcastle, where production of the Armstrong gun was already in full swing at his Elswick Ordnance Works on the Tyne. On the urging of his business manager Stuart Rendel, the firm then began selling guns to foreign powers.

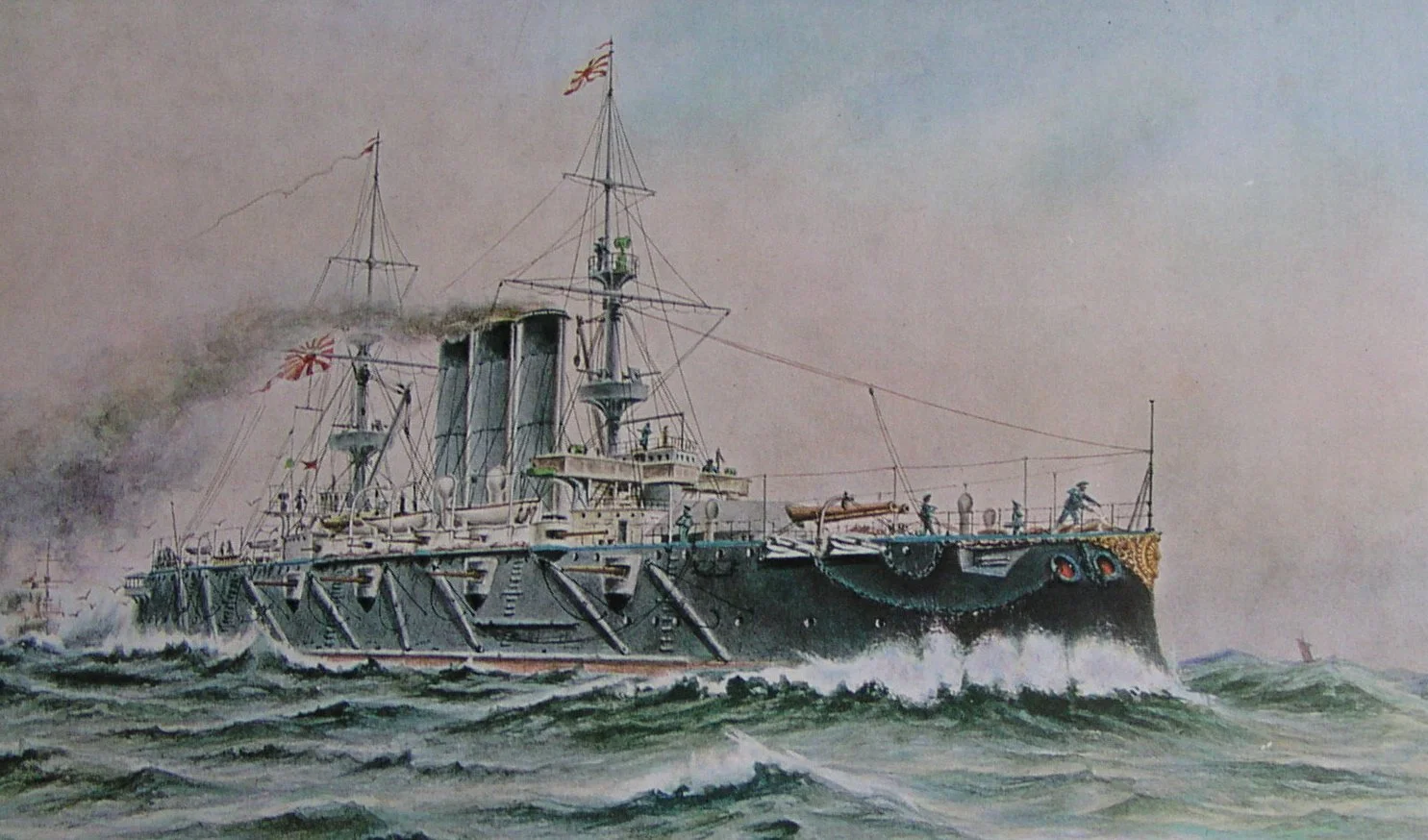

Gun design at Elswick became increasingly sophisticated and the factory began producing weapons for naval use. This led Armstrong into a partnership with the shipbuilder Charles Mitchell and the new firm was soon building gunboats for the defence of coastal waters. As demand expanded, the shipbuilding operation grew and grew and, starting with the Esmeralda class, Armstrong Mitchell went on to build ships for all the world’s emerging maritime nations, from Chile to Italy to Japan.

On her launch in 1899, the battleship Hatsuse, built by Armstrong Whitworth at the company's Elswick shipyard for the imperial navy of Japan, was the largest warship ever seen on the Tyne.

Hydroelectricity

It is almost 150 years since the first effective incandescent lamp, or light bulb, was invented by the Newcastle chemist Joseph Wilson Swan. Swan was a friend of William Armstrong, the master of Cragside, who had created at his Northumberland home the world's first hydroelectric power station. Armstrong had dammed rivers to make lakes and artificial waterfalls that would drive a Siemens dynamo.

In December 1880, Swan asked Armstrong if he could try out his new invention at Cragside. ‘As far as I know, Cragside was the first house in England properly fitted up with my electric lamps,’ said Swan later. ‘It was a delightful experience for both of us when the gallery was first lit up. The speed of the dynamo had not been quite rightly adjusted to produce the strength of current required. It was too fast, and the current too strong. Consequently, the lamps were far above their normal brightness – but the effect was splendid, and never to be forgotten.’

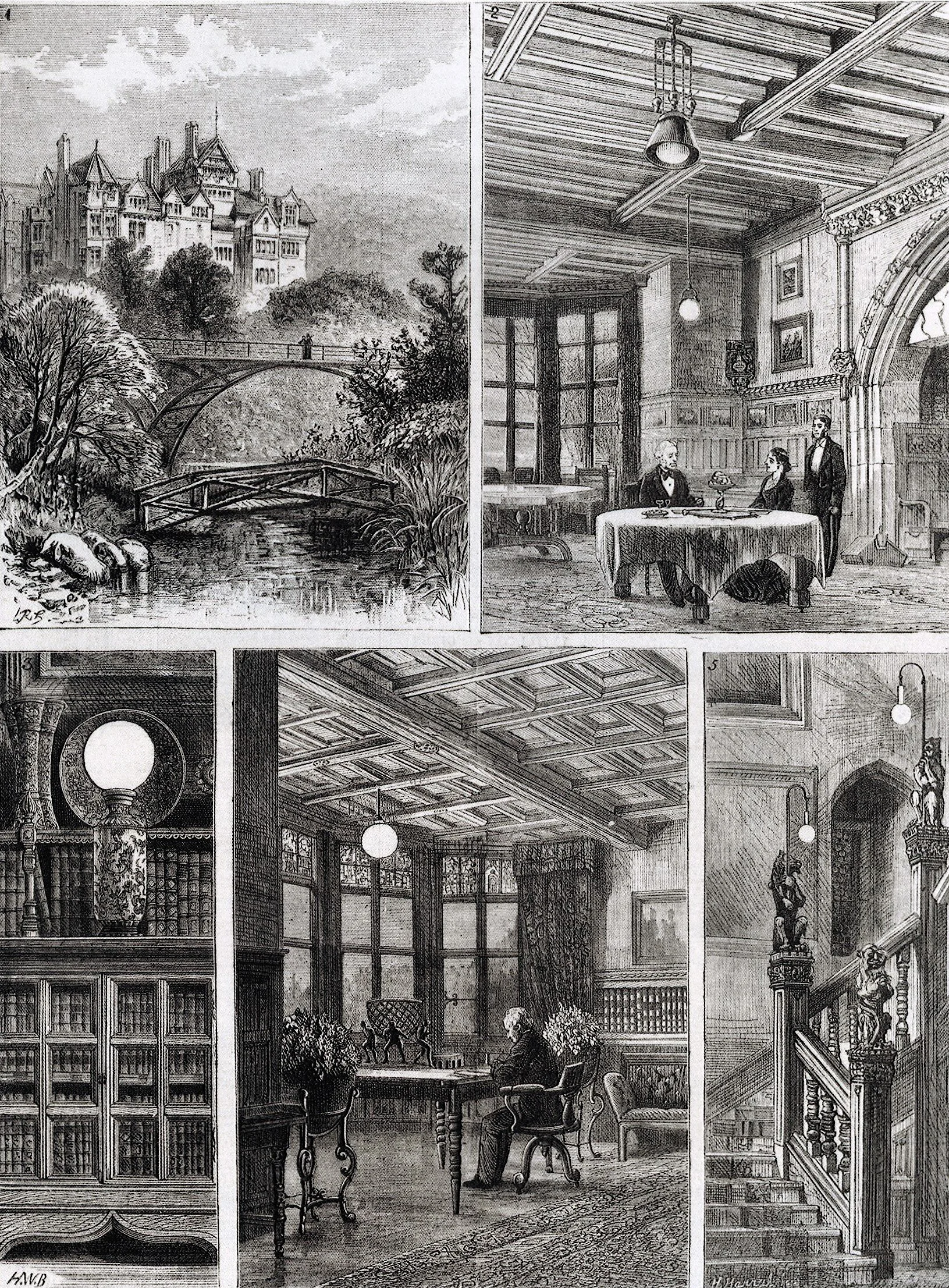

The Graphic newspaper later published an article on the phenomenon, using the illustrations shown here.

Lighting the world with renewable energy

Swan had already demonstrated the workings of the new electric light at Newcastle's Literary & Philosophical Society (the Lit & Phil). After he had finished speaking, he gave the signal for the 70 gas jets that usually lit the room to be extinguished.

‘Then – with a suddenness which in those days seemed quite magical,' said an observer, 'he transformed darkness into light by switching on 20 of his own lamps, producing an illumination which, as compared with gas light, had a very brilliant effect.’

It was the first time that the interior of any public building, in Europe at least, had been lit by incandescent electric lamps. Swan later formed a company with his great American rival, Thomas Edison, to provide electric lighting on a commercial scale to the world’s most industrialized countries.

After his experiments with Joseph Swan, William Armstrong published the following account in the Graphic newspaper:

'The following particulars of a successful application of Swan's Electric Lamps to the lighting of a country house will probably be interesting to many of your readers.

‘The case has novelty, not only in the application of this mode of lighting to domestic use, but also in the derivation of the producing power from a natural source – a neighbouring brook being turned to account for that purpose. The brook, in fact, lights the house, and there is no consumption of any material in the process.'

An illustration of April 1881 in the Graphic shows the iron footbridge over the Debdon Burn (the source of Cragside’s electrical power) and three illuminated interiors: the dining room, the library and the staircase hall.